THE MACHINE HAS TO BE WRONG

It's unfair, in a way.

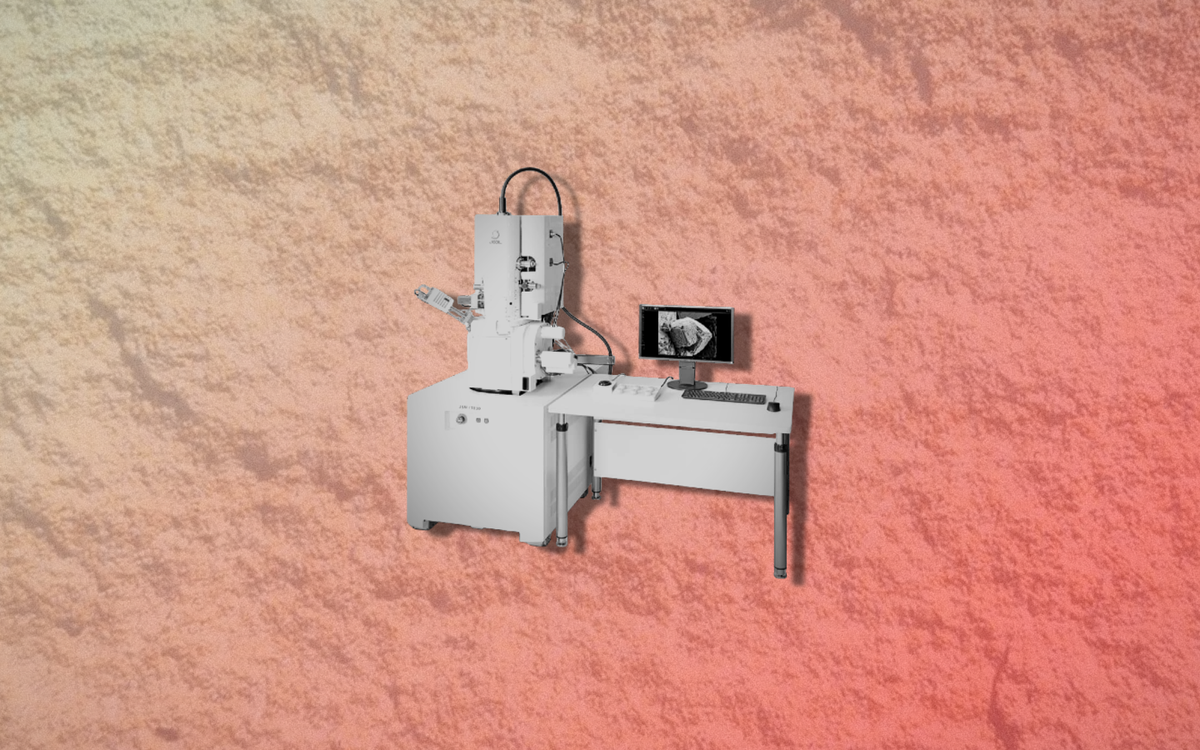

Up the corridor come your friend and the kid they look after, their kid, excuse the phrasing, awakening as they stomp towards you the memory that you told them that they could come by to visit you any time at work, and here they've come to collect - and there's no way out of it because you did offer, and enthusiastically, because at the time you offered you were feeling generous, having just received some good news (which was that your sister, after years of working a junior job at a place she loved but which had six opportunities to give her a promotion but passed her over every time, and underpaid her, had finally got a better job). It was brunch on a sunny morning and you wanted to give somebody a gift. You practically invited this. You did invite it. On top of that your friend has an expression on her face that says, Please let something happen easily for me, and she's trailing her kid, and the kid - look, they're a sweet kid - beautiful kid. But, well, honestly, they're a hypochondriac - they're insecure, and they invent afflictions. They're always nursing something. There's always a limp. Just now they're coming up the corridor, shaking their hand a little, examining their knuckles, muttering something under their breath, looking back distractedly over their shoulder like the culprit is behind them but they're dealing with it, stoic and sensible, above making a fuss. You give them a little wave. "You made it!", you say, and your friend sighs, and the kid solemnly digs a rock out of a little silk bag they’re clutching in one sweaty hand and places it on the desk next to you. "Ah," you say, picking it up and studying it. You brush it with a thumb, hold it up to catch the light, wink at the kid and sniff it and you say, "And what's your hypothesis?" And the kid says, "Well, it's hard to say... it could be anything..." And you say, "Well, maybe not anything. What type of rock might it be?" And they say, "Metamorphic maybe?" And you say, "That'd be my guess." You take the rock and slide it under a microscope, and it's unusual, the rock, and you turn it over in your fingers, and say, "Hmmm." And then you stand up, "Be right back," and you take it through the greying saloon doors into the lab and run some tests on it. You scrape off some particles, saw off one end for a cross section, slosh the particles in with various dyes and solutions, slip some chunks into the electron microscope, and what you find out is nothing - it's not responding to any of the normal tests. Unknown material, you think, rolling your eyes, clicking your tongue with irritation, and you make your way around the instruments, mouthing encouragement to the radiometer, running a contemplative hand over the magnet array, and you wait, and while you wait you hand it to a colleague and say, "Hey, what do you make of this? It's an unknown material," And she peers at it and tells you she'll run some tests. Of course you're not really thinking, wow, we got a new element here - you're not up to that. What you're up to is God, it'll be a flop if I have to go back out there and tell my friend's hypochondriac kid I don't know what the rock is - what kind of scientist will I look like? And they might cry - they’ll probably cry, and I don’t know what to do with a crying kid. Damn it. Well, I could take them to get a free X-ray so they can see their bones? And reluctantly you go back out and say, "Fascinating rock you brought in - I've just shown it to my colleague, and she's stumped. But we'll see what tale the radiometer and the magnets can tell." And the kid gets this look like, Big surprise. Like - Disappointed again. And in honesty this is your weakness. Maybe it’s impostor syndrome, maybe it’s just deeply-felt insecurity that your natural giggle and willingness to horse around in the lab, to play the fool, even, as some have characterised it, mean that your professional opinion carries less weight. You look at the kid, and maybe there’s a sourness in your expression because they get this stubborn look on their face. Their eyes are half-closed, jaw sticking out, a little slack, a sullen tint to the whole thing. Telepathically you’re telling them Don’t cry, don’t cry, and you probably don’t need to make intense eye contact for telepathy to work, but that’s what you’re doing and maybe in retrospect that exacerbates the situation because suddenly there’s a film over their eyes and they’re flushing a little. That’s when the real miracle happens - not telepathy, but the fact that it doesn’t piss you off. A magic filter of sympathy descends. You see a kid who cares enough about rocks to be a nuisance about them, charmless, single-minded, but passionate - you feel a pang. They’re still staring right into your eyes, probably thinking “Why isn’t this fool analysing my beautiful rock,” and, well - that’s me, you’re thinking, emotion welling up as you look at them. You’ve been gazing into each other’s eyes long enough for your friend to give you a look like, Hello? Anyone home? And you kind of shake your head like a basset hound after a drink and bustle back through the saloon doors, thinking this is it - my moment to strike a blow for innocence, for inquiry, for not being a boring stressed out guy when a kid displays enthusiasm for science - to take up the instruments to define the rock or die trying. The magnet array - inconclusive. Your colleague - apologetic. Fake levity in her tone, she says, "Wow, this rock is really something. I can't figure out what it is - maybe it really is an unknown material? Ha." And then you check the radiometer and you're sort of taken aback - so much that when your friend and her kid stick their heads through the saloon door and ask how you're going you don't notice them until they're right next to you, looking at the readout that says that based on the decay of the isotopes and whatnot, the atoms and so on, the rock could be seven billion years old, which is impossible. Tap, tap, tap. You're fiddling around with the settings. You're checking if there's a decimal place missing. "Thing’s busted?" You're calling out to your colleague, but it isn't. Diagnostic scan complete. All systems working. "The Earth is likely 4.6 billion years old," your friend's kid is saying, which you know - you know that. They’re looking at you, forgetting to nurse the hand they were pretending they’d hurt, watching, waiting for you to explain it all, but you can’t. And that's why the machine has to be wrong. Because 4.6 billion is the upper limit. And if the machine is right it means that this weird looking dirty rock, which, after all, doesn't look so weird - only weird if you know rocks, and can tell different types of rock based on sight - this glob of mineral, made of an unknown substance, is older than the Earth, maybe older than the sun, had been floating through gas sprays, nebulas and so on for billions of years until it congealed with the rest of the dust into planet Earth and waited to be found by your friend’s kid. And that can't be true. It's unfair, in a way. Caught between an infinite number of rocks and a child's magical curiosity about the natural universe is you, the humble translator, trying to stick a plug into a socket with a cord that’s too short. The kid's standing near your elbow, holding a piece of the rock you’d set down on the counter and looking at it with reverence and fear like it’s a sorcerer’s gem. "Where was this?", you ask, and the kid says they found it under the house, in a deep pit, a hole that they dug themselves, and your friend is nodding tiredly - they dug it up themselves, I saw it. But that can't be true.